Managing Power

The power-management functionality of the I/O Kit aims to minimize the power consumed by a computer system, behavior that is especially important for portable computers where battery life is a crucial feature. Power management also imposes an orderly sequence of actions, such as saving and restoring state, when a system (or a part of it) sleeps or wakes.

This chapter focuses on power management for in-kernel drivers that manage hardware. Read this chapter to learn about power management in Mac OS X and to find out what level of power-management support you need to provide and how to implement it. Although power management is a complex technology, the majority of in-kernel drivers need to implement only the most basic functionality to participate successfully in Mac OS X power management.

Note: If you’re developing an application that accesses hardware, such as a user-space driver for a digital camera, scanner, webcam, or tape drive, you probably do not need to perform any power-management tasks. For more information on developing applications that behave as user-space drivers, including information on how to set up your application to receive power-event notifications, see Accessing Hardware From Applications.

The precise set of power-management responsibilities your driver must fulfill depends on factors such as how much support your driver’s superclass provides, whether your device receives power from a system bus (such as PCI), and to what power events your driver needs to respond.

If you’re unfamiliar with power management in Mac OS X, you should begin by reading the following three sections:

“Power Events” which explains what power events are and how they affect your device

“The Power Plane: A Hierarchy of Power Dependencies” which describes how Mac OS X monitors the power relationships among devices, drivers, and other objects

“Devices and Power States” which defines devices and power states in power-management terms

Then, all driver developers should read “Deciding How to Implement Power Management in Your Driver” to find out what to do next. After you decide what type of power management you need to implement, read “Implementing Basic Power Management” and, if appropriate, “Implementing Advanced Power Management”

Power Events

Before you consider how to implement power management in your driver, you need to understand what power events are and how they can affect your device. In Mac OS X, power events are transitions to and from the following states:

Sleep

Wake

Shutdown or restart

All drivers must respond to sleep events. Mac OS X defines different types of sleep, which can occur for different reasons. For example, system sleep occurs when the user chooses Sleep from the Apple menu or closes the lid of a laptop; idle sleep occurs when there has been no device or system activity during the interval the user selects in the Energy Saver preferences. To your driver, however, all sleep events appear identical. The important thing to understand about a sleep event is that your device may be powered off when the system sleeps, so your driver must be prepared to initialize the device when it is awakened.

All drivers must respond to a system wake event by powering on. Wake can occur when the user hits a key on the keyboard, presses the power button, or when the computer receives a network administrator wake-up packet. On wake, drivers should perform the appropriate restoration of device state.

Device drivers do not have to respond to shutdown and restart events. A driver can choose to get notification of an impending shutdown or restart using the technique described in “Receiving Shutdown and Restart Notifications” but it’s important to understand that no driver can prevent a shutdown event.

Another type of event is a device power-up request, which occurs when some object in the system requires an idle or powered-off device to be in a usable state. A device power-up request notification uses most of the same mechanisms as sleep and wake notifications. Although most drivers do not need to know about device power-up requests, some drivers might need to implement them and even make such requests themselves. For more information about this, see “Initiating a Power-State Change”

The Power Plane: A Hierarchy of Power Dependencies

Mac OS X tracks all power-managed devices in a tree-like structure, called the power plane, that captures the power dependencies among devices. A device, usually a leaf object in the power plane, generally receives power from its ancestors and may provide power to its children. For example, because a PCI card depends for power on the PCI bus to which it’s attached, the PCI card is considered to be a power child of the PCI bus. Likewise, the PCI bus is considered to be the power parent of the devices attached to it.

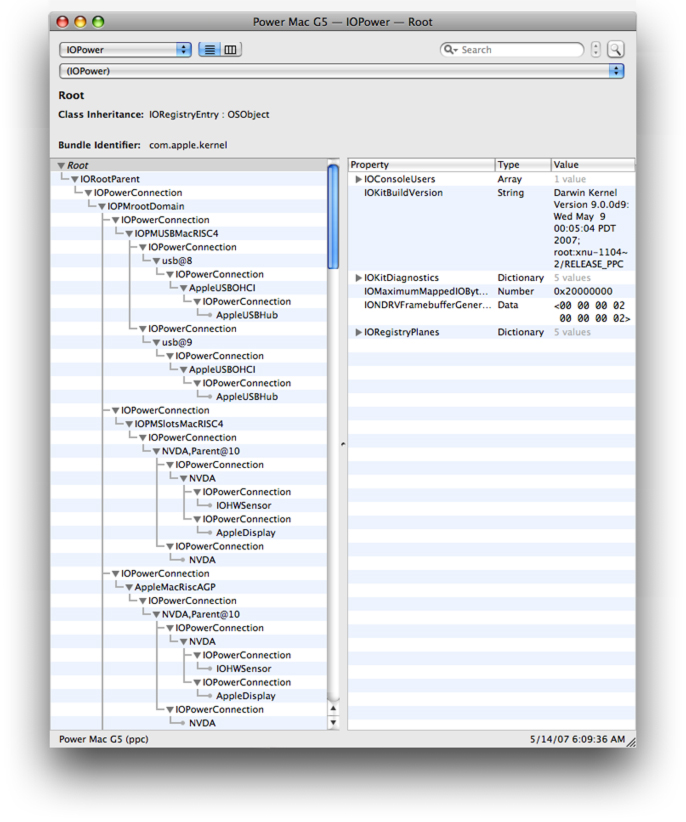

The power plane is one of the planes of the I/O Registry. As described in “The I/O Registry” the I/O Registry is a dynamic database of device and driver objects that expresses the various provider-client relationships among them. To view the power plane in a running system, open the I/O Registry Explorer application (located in /Developer/Applications/Utilities) and choose IOPower from the pop-up menu. You can also enter ioreg -p IOPower at the command line to see a representation of the current power plane. Figure 9-1 shows the power plane in a Power Mac G5 running Mac OS X v10.5.

In Figure 9-1 you can see the root of the power plane, an object called IOPMrootDomain, and objects that represent devices and drivers. You can ignore the many IOPowerConnection objects, which represent power connections, because these objects are of interest only to internal power-management objects and processes.

Devices and Power States

The fundamental entity in power management is the device. From a power-management perspective, a device is a unit of hardware whose power consumption can be measured and controlled independently of system power. A device can also have some state that needs to be saved and restored across changes in power. In power-management terms, “device” is synonymous with the device-driver object that controls it.

A device must have at least two power states associated with it—off and on. A device may also have intermediate states that represent some level of power between full power and no power. These states are described in a power-state array you create in your driver. (You learn how to create this array and provide power-state information in step 3 in “Implementing Basic Power Management”) The power-management functionality of the I/O Kit uses these states to ensure that all drivers in the power plane receive the power they require. Each power state is defined by the device’s capabilities when in that state:

A device that is on uses maximum power and has complete functionality.

A device that is off uses no power and has no functionality.

A device can be in a reduced-power state in which it is still usable, but at a lower level of performance or functionality.

A device can be in an intermediate state in which it is not usable, but retains some configuration or state.

The power-management functionality of the I/O Kit associates several attributes with each power state of a device. A device driver must set these attributes to ensure that accurate information about the device’s capabilities and requirements is available.

The power-state attributes provide the following information:

The capability of the device while in a given state

The device’s power requirements of its power parent

The power characteristics the device can provide to its power children

The version of the power-state structure the device uses to store its power-state information

Deciding How to Implement Power Management in Your Driver

To participate in Mac OS X power management, most in-kernel drivers need only ensure that their devices respond appropriately to system sleep and wake events. Some in-kernel drivers might need to perform other tasks, such as implementing an idle state or taking action at system shutdown, but these drivers are not typical. Reflecting this distinction, Mac OS X power management defines two types of drivers:

A passive driver implements basic power management to respond to system power events; it does not initiate any power-related actions for its device.

An active driver implements basic power management to respond to system power events, but it also implements advanced power management to perform tasks such as deciding when the device should become idle, changing the device’s power state, or processing prior to system shutdown.

An example of a passive driver is the AppleSmartBatteryManager driver present in most Macintosh laptop computers. The AppleSmartBatteryManager driver provides battery-status information to the battery-status menu bar item; when the system is about to sleep, the driver simply stops polling the battery for status information. A good example of an active driver is the built-in audio chip driver, because it performs its own idleness determination to allow the audio hardware to power off when it is not in use. If there is no sound coming out of a laptop's or desktop's internal speakers, the audio hardware will drop into a low power mode until it is needed.

As you can imagine, a passive driver is much easier than an active driver to design and implement. Essentially, a passive driver implements one virtual method and makes between three and five calls to participate in power management. The responsibilities of an active driver, on the other hand, begin with those of a passive driver, but increase with each additional task the driver needs to perform.

Some I/O Kit families provide various levels of built-in power-management support to driver subclasses. For example, the Network family (IONetworkingFamily) performs some of the power-management initialization tasks for a subclass driver, leaving the driver to perform other device-specific power-management tasks.

Before you begin designing your driver’s power-management implementation, you should look up your I/O Kit family in “I/O Kit Family Reference” to find out if the family provides any power-management support or requires subclasses to perform different or additional tasks. Be aware, however, that any I/O Kit family that provides power-management functionality may still require you to implement some parts of it. The following I/O Kit families provide some type of power-management functionality:

Audio family (described in “Audio”)

FireWire family (described in “FireWire”)

Network family (described in “Network”)

PC card family, which includes Express Card devices (described in “PC Card”)

PCI family (described in “PCI and AGP”)

SCSI Architecture Model family (described in “SCSI Architecture Model”)

USB family (described in “USB”)

Even if your driver is a subclass of an I/O Kit family that does not provide any power-management support, or if your driver is a direct subclass of IOService, it can still be a passive power-management participant as long as it only responds to system-initiated power events. If, on the other hand, your driver needs to determine when your device is idle or perform pre-shutdown tasks, you must implement advanced power management.

If you decide to develop a passive driver, you should read “Implementing Basic Power Management” to learn how to participate in power management and respond to sleep and wake events. You do not need to read any other sections in this chapter.

If your driver needs to be an active power manager, you should also read “Implementing Basic Power Management” Then you should read “Implementing Advanced Power Management” for guidance on implementing specific tasks.

Implementing Basic Power Management

As defined in “Deciding How to Implement Power Management in Your Driver” a passive driver only responds to sleep and wake events; it does not initiate any power state–changing activity. Your passive driver must do the following things to handle sleep and wake:

Get attached into the power plane so you receive power-change notifications and to ensure that your device’s power dependencies are considered when it is told to sleep and wake.

Power dependencies affect the ordering of sleep and wake notifications. Specifically, your driver is told to sleep before its power parent is told to sleep, and your driver is told to wake after its power parent is told to wake.

Save hardware state to memory before system sleep and restore state during wake.

You are responsible for writing code to do this.

Prevent all hardware accesses while your device is preparing for sleep.

You can return an error to any I/O request you receive while your device is going to sleep or you can block all incoming threads using a gating mechanism, such as

IOCommandGate, on your work loop (see “Work Loops ” to learn more about work loops).

To participate in power management so that you receive notifications of power events, ensure your driver is correctly attached into the power plane, and handle power-state changes, you make a few calls and implement one virtual method. The IOService class provides all the methods described in this section. Follow the steps listed below to implement basic power management in your driver.

Initialize power management using

PMinit. ThePMinitmethod allocates internal power-management data structures that allow internal processes to track your driver.In your driver’s

startroutine, after the call to your superclass’sstartmethod, make the following call:PMinit();

Get attached into the power plane using

joinPMtree. ThejoinPMtreemethod attaches the passed-in driver object into the power plane as a child of its provider.In your driver’s

startroutine, after the call toPMinitand before the call toregisterPowerDriver(shown in step 3), calljoinPMtreeas shown below:provider->joinPMtree(this);

Provide information about your device’s power states and register your driver with power management.

First, declare an array of two structures to contain information about your device’s off and on states. The first element in the array must contain the structure that describes the off state and the second element of the array must contain the structure that describes the on state. Typically, a driver switches its device to the off state in response to a sleep event and to the on state in response to a wake event, as described in “Power Events”

In your driver’s

startroutine, after the call tojoinPMtree, fill in twoIOPMPowerStatestructures, as shown below:// Declare an array of two IOPMPowerState structures (kMyNumberOfStates = 2).

static IOPMPowerState myPowerStates[kMyNumberOfStates];

// Zero-fill the structures.

bzero (myPowerStates, sizeof(myPowerStates));

// Fill in the information about your device's off state:

myPowerStates[0].version = 1;

myPowerStates[0].capabilityFlags = kIOPMPowerOff;

myPowerStates[0].outputPowerCharacter = kIOPMPowerOff;

myPowerStates[0].inputPowerRequirement = kIOPMPowerOff;

// Fill in the information about your device's on state:

myPowerStates[1].version = 1;

myPowerStates[1].capabilityFlags = kIOPMPowerOn;

myPowerStates[1].outputPowerCharacter = kIOPMPowerOn;

myPowerStates[1].inputPowerRequirement = kIOPMPowerOn;

In some drivers, you might see this step implemented in code similar to the following:

static IOPMPowerState myPowerStates[kMyNumberOfStates] = {{1, kIOPMPowerOff, kIOPMPowerOff, kIOPMPowerOff, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0},{1, kIOPMPowerOn, kIOPMPowerOn, kIOPMPowerOn, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}};

Then, still in your driver’s

startroutine, register your driver with power management usingregisterPowerDriver. TheregisterPowerDrivermethod tells power management that the passed-in driver object can transition the device between the power states described in the passed-in array. After you fill in theIOPMPowerStatestructures, callregisterPowerDriverwith your power-state array as shown below:registerPowerDriver (this, myPowerStates, kMyNumberOfStates);

Handle power-state changes using

setPowerState. While your driver is running, you perform tasks that handle sleep and wake event notifications in your implementation of the virtualIOServicemethodsetPowerState. An example of how to do this is shown below:IOReturn MyIOServiceDriver::setPowerState ( unsigned long whichState, IOService * whatDevice )

// Note that it is safe to ignore the whatDevice parameter.

{if ( 0 == whichState ) {// Going to sleep. Perform state-saving tasks here.

} else {// Waking up. Perform device initialization here.

}

if ( done )

return kIOPMAckImplied;

else

return (/* a number of microseconds that represents the maximum time required to prepare for the state change */);

}

If you return

kIOPMAckImplied, you signal that you’ve completed the transition to the new power state. If you do not returnkIOPMAckImpliedand instead return the maximum amount of time it takes to prepare your device for the power-state change, you must be sure to callacknowledgeSetPowerStatewhen you have finished the power-state transition. If you do not callacknowledgeSetPowerStatebefore the length of time you specify has elapsed, the system continues with its power-state change as if you had returnedkIOPMAckImpliedin the first place.Note: If you are developing a driver for Mac OS X v10.5 or later, you may perform all necessary processing to prepare for the state change in the

setPowerStatemethod before you returnkIOPMAckImplied. In other words, you do not have to return an estimate of how long the processing will take, perform the processing in another method, and callacknowledgeSetPowerStatewhen the processing is finished.Unregister from power management when your driver unloads using

PMstop. ThePMstopmethod handles all the necessary cleanup, including the removal of your driver from the power plane. BecausePMstopmay put your hardware into its off state, be sure to complete all hardware accesses before you call it.Important: This step is crucial. If you neglect to call

PMstop, you will probably cause a leak and you might cause a system panic the next time the computer wakes up.In your driver’s

stoproutine, after you finish all calls that might access your hardware, callPMstopas shown below:PMstop();

Implementing Advanced Power Management

This section delves deeper into the power-management functionality of the I/O Kit. The vast majority of driver developers do not need to understand the information in this section because basic power management (as described in “Deciding How to Implement Power Management in Your Driver”) is sufficient for most devices. If your device can be passively power managed, read “Implementing Basic Power Management” instead.

You should read this section if your driver needs to perform advanced power-management tasks, such as determining device idleness, taking action when the system is about to shutdown, or deciding to change the device’s power state. Of course, active drivers share some tasks with passive drivers, namely the initialization and tear-down of power management. Before you read about the tasks in this section, therefore, you should glance at the steps in “Implementing Basic Power Management” to learn how to initialize and terminate power management in your driver. Even if your driver must perform advanced power-management tasks, it still needs to call PMinit, joinPMtree, registerPowerDriver, and PMstop and implement setPowerState, as shown in “Implementing Basic Power Management”

This section covers several tasks an active driver might need to perform. Although few active drivers will perform all the tasks, most will perform at least one. Each task is accompanied by a code snippet to help you implement it in your driver.

Defining and Using Multiple Power States

As described in “Devices and Power States” information about a device’s power states and capabilities must be available to I/O Kit power management. Although most devices have only the two required power states, off and on, some devices have additional states. As shown in step 3 of “Implementing Basic Power Management” you construct an array of IOPMPowerState structures, each of which contains information about the device’s capabilities in each power state.Table 9-1 describes the fields in the IOPMPowerState structure, which is defined in the IOPM.h header file.

Field | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Version number of this structure. | 1 |

| The capability of the device in this state. | An |

| The power supplied in this state. | An |

| The input power required in this state. | An |

| Average power consumption (in milliwatts) of a device in this state. | 0 |

| Additional power consumption (in milliwatts) from a separate power supply, such as a battery. | 0 |

| The power consumed by a device (in milliwatts) in entering this state from the next lowest state. | 0 |

| The time (in microseconds) required for a device to enter this state from the next lower state; in other words, the time required to program the hardware. | 0 |

| The time (in microseconds) required to allow power to settle after entering this state from the next lower state. | 0 |

| The time (in microseconds) required for a device to enter the next lower state from this state; in other words, the time required to program the hardware. | 0 |

| The time (in microseconds) required to allow power to settle after entering the next lower state from this state. | 0 |

| The power (in milliwatts) that a power parent in this state is electronically able to deliver to its children. | 0 |

As shown in Table 9-1 the values of some fields may be provided by an IOPMPowerFlags flag. Table 9-2 shows the IOPMPowerFlags flags you are likely to use.

Flag | Description |

|---|---|

| The device is in the full-power state. |

| The clients of the device can use it in this state. |

| The device is capable of its highest performance in this state. |

| The PCI auxiliary power supply is on (used only by devices in the PCI family). |

Power management has the following requirements for the array of IOPMPowerState structures you construct in your driver’s start method:

The

IOPMPowerStatestructure describing your device’s off state must be the first element in the array.The

IOPMPowerStatestructure describing your device’s on (that is, full power) state must be the last element in the array.You can define any number of intermediate power states, but the

IOPMPowerStatestructures describing them must not be the first or last elements of the array.

After you construct the power-state array to these specifications, call registerPowerDriver, passing in a pointer to the array and the number of power states. Listing 9-1 shows one way to do this. It also shows the driver creating a work loop and setting up a command gate to synchronize the power state-change code, which is described in “Changing the Power State of a Device”

Listing 9-1 Building the power-state array and registering the driver

enum { |

kMyOffPowerState = 0, |

kMyIdlePowerState = 1, |

kMyOnPowerState = 2 |

}; |

static IOPMPowerState myPowerStates[3] = { |

{1, kMyOffPowerState, kMyOffPowerState, kMyOffPowerState, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}, |

{1,kIOPMPowerOn, kIOPMPowerOn, kIOPMPowerOn, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}, |

{1,kIOPMPowerOn, kIOPMPowerOn, kIOPMPowerOn, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0} |

}; |

bool PMExampleDriver::start(IOService * provider) |

{ |

/* |

* Create a work loop and set up synchronization |

* using a command gate. |

*/ |

fWorkloop = IOWorkLoop::workLoop(); |

fGate = IOCommandGate::commandGate(this); |

if (fGate && fWorkloop) { |

fWorkloop->addEventSource(fGate); |

} |

* Initialize power management, join the power plane, |

* and register with power management. |

*/ |

PMinit(); |

provider->joinPMtree(this); |

registerPowerDriver(this, myPowerStates, 3); |

} |

Changing the Power State of a Device

A driver is responsible for changing the power state of its device. Most power-state change requests come from power management when the system is about to sleep or wake. It’s also possible for an active driver to become aware of the need to change its device’s power state and initiate the request. The following sections describe both tasks.

Responding to a Power State–Change Request

As with a passive driver, an active driver must override the setPowerState method and change the power state of its device when it is instructed to do so. The ordinal value passed in to setPowerState is an index to the power-state array for the device.

If you’re developing a driver to run in versions of Mac OS X prior to v10.5, you must perform only the minimum processing required to change the power state of your device in your setPowerState method. Any additional processing must be performed outside of the setPowerState method and followed by a call to acknowledgeSetPowerState when it is finished. This is described in step 4 of “Implementing Basic Power Management”

If, on the other hand, your driver will run in Mac OS X v10.5 and later, you can perform all necessary processing in your setPowerState method before you return kIOPMAckImplied. It’s important to understand, however, that power management calls the setPowerState method from a thread-call context. In other words, power management does not perform any automatic synchronization using your driver’s work loop. Therefore, it’s essential that you continue to use a command gate or other locking primitive to ensure that access to your device’s state is serialized.

As soon as your driver returns kIOPMAckImplied or calls acknowledgeSetPowerState after additional processing, power management marks the power change as completed. Thus it’s important for all drivers, regardless of the version of Mac OS X they target, to avoid reporting a power change as complete until the power-state of the device has actually changed. It’s possible that other power changes depend on your hardware having completed its power change before you call acknowledgeSetPowerState.

Initiating a Power-State Change

An active driver might become aware of the need to change its device’s power state, either through mechanisms of its own or through some other object. The IOService class provides three methods that assist in this task:

makeUsablechangePowerStateTochangePowerStateToPriv

Any object in the driver stack, including a user client (described in “The Device-Interface Mechanism ”), can request that a dormant device be made active by calling the makeUsable method on the device’s driver. The makeUsable method is interpreted as a request to put the device in its highest power state.

An active driver typically calls the changePowerStateTo method once in its start method, to set an initial power state. Later, when it wants to change its device’s power state, an active driver calls the changePowerStateToPriv method, passing in the desired power state. An active driver might do this to shut down parts of the hardware that are not currently being used.

Important: Even though the makeUsable, changePowerStateTo, and changePowerStateToPriv methods are asynchronous and return immediately, you must block all hardware access until you receive the call to your setPowerState method. Before your setPowerState method is called, you cannot be certain that your device is in a usable state. Because of this, these functions should be called in a work-loop context.

Power management uses the states passed in to changePowerStateTo and changePowerStateToPriv to determine the device’s new power state. Specifically, power management selects as the new power state the highest value of the following three values:

The power state set by

changePowerStateToPrivThe power state set by

changePowerStateToThe highest of all power states required by the driver’s power children

The following code snippet shows how a driver can get the device’s current power state (using the getPowerState method introduced in Mac OS X v10.5) and then request a power-state change with changePowerStateToPriv.

Implementing Idleness Determination and Idle Power Saving

When a device is idle, it can be powered down to conserve system power, which is especially important for laptop computers running on battery power. You should implement idle power saving in your device if:

Access to your device is intermittent, and the device is often left unused for minutes, hours, or days at a time.

Your device consumes a significant amount of power, and putting it in a low power state when possible results in substantial power savings.

To implement idle power saving, you must determine when your device is idle and specify how long the period of idleness should last before your device powers off. You determine idleness by supplying device-access information to the IOService superclass, which uses this information, in conjunction with the idleness period you specify, to tell your device to power off at the appropriate time. The IOService class provides two methods an active driver uses to do this:

activityTickle. On your device’s access path, you callactivityTickleevery time your driver or any other client (including an application) triggers a hardware access. This allows power management to confirm that your device is in a usable state and to track the most recent access times for your device.setIdleTimerPeriod. You callsetIdleTimerPeriodto specify the duration of a watchdog timer that tracks how long your device can be idle at full power before it should be powered down. By setting the duration of the idle period, you effectively start a countdown that begins after each device access.

When the idle period expires without any device activity, power management calls your implementation of the setPowerState method to lower your device’s power state. See “Changing the Power State of a Device” for more information on how to implement this method.

Of course, you must respond to any device-access request you receive while your device is powered off by first setting your device to its full-power state. Because you call activityTickle on your device’s access path, power management is immediately alerted to the fact that some entity is requesting access to a device that is currently powered off. When this happens, the IOService superclass automatically calls makeUsable on your device, which ultimately results in a call to your implementation of the setPowerState method.

Important: As described in “Initiating a Power-State Change” you must block all hardware accesses until your setPowerState implementation is called, because you cannot be certain that your device is in a usable state until that time. The best way to do this is to use a work loop to serialize hardware access.

The following steps outline the process of idleness determination:

Specify how long your device should remain in a high-power state while idle. Typically, one minute is an appropriate interval.

Call

setIdleTimerPeriod, passing in the idle interval in seconds, as shown below:setIdleTimerPeriod ( 60 );

Inform power management every time an entity (including your driver) initiates a device access.

In your driver’s device-access path, call

activityTickle, as shown below:activityTickle ( kIOPMSuperclassPolicy1, myDevicePowerOn );

As shown above, the first parameter to

activityTickleiskIOPMSuperclassPolicy1, which indicates that theIOServicesuperclass will track device activity and take action when the idle period expires. The second parameter specifies the power state required for this activity, typically the on state.When the idle timer expires, the

IOServicesuperclass checks whether there has been any device activity since the last idle timer expiration. The superclass determines this by checking whenactivityTickle(kIOPMSuperclassPolicy1) was last called.If there has been device activity since the last timer expiration, the

IOServicesuperclass restarts the timer. If no device activity has occurred, theIOServicesuperclass callssetPowerStateon your driver to power down the device to the next lowest state.

Optional: A driver may implement variable idle timeout behaviors by overriding the IOService method nextIdleTimeout. To do this, your implementation of nextIdleTimeout should return how many "seconds from now" the device should move into its next lowest power state.

nextIdleTimeout to dynamically adjust the display’s idle-sleep timeouts. If the user moves the mouse very soon after the display dims, the display driver remembers this and increases the timeout period, effectively waiting a longer time before it initiates the next several display-dim events.After your device has been powered down to a lower state through this process, a new activityTickle invocation causes power management to raise the device’s power to the level required for the activity. If the device is already in the correct state, the superclass simply returns true from the call to activityTickle ( kIOPMSuperclassPolicy1 ); otherwise, the superclass returns false and proceeds to make the device usable.

Although the return value of activityTickle indicates whether the device is in a usable power state, it’s better to keep track of your device’s current power state in your driver than to rely on the activityTickle return value for this information. This is because activityTickle is not called on the power management work loop and a device’s power state might change before activityTickle returns.

Receiving Notification of Power-State Changes in Other Devices

In some cases, your driver might need to be notified when another driver changes its device’s power state. I/O Kit power management brackets each change to the power state of a device with a pair of notifications. These notifications are delivered through invocations of the IOService virtual methods powerStateWillChangeTo and powerStateDidChangeTo. You can implement these methods to receive the notifications and prepare for the changes.

Your driver can register its interest in another driver, as long as the following is true:

The driver in which your driver is interested must be attached into the power plane.

Your driver must be a C++ subclass of

IOService, but it does not have to be attached into the power plane itself.

To find out when another driver changes its device’s power state, follow these steps in your driver:

Call the

IOServicemethodregisterInterestedDriver. This ensures that power management will notify your driver when it sends out power-change notifications.Implement the virtual

IOServicemethodpowerStateWillChangeTo. This method is called by the device’s driver when it is about to change the device’s power state.If your driver is prepared for the change, it should return

kIOPMAckImplied; if it needs more time to prepare, it should return an upper limit on the time required (in microseconds).If your driver returns a number representing the maximum preparation time needed, it should call the

acknowledgePowerChangemethod when it is prepared. If it does not do this, and the time requested for preparation elapses, the other driver carries on as if your driver had acknowledged the change. This behavior prevents power-state changes from stalling because of failing drivers.Important: The

powerStateWillChangeTomethod is not the place to perform any tasks related to the actual changing of the power state. Such tasks should be performed in thesetPowerStatemethod, which is described in “Responding to a Power State–Change Request”Implement the virtual

IOServicemethodpowerStateDidChangeTo. This method is called by the device’s driver after the power-state changed is complete.After the change to power occurs and the power has settled to its new level, power management broadcasts this fact to all interested objects via the

powerStateDidChangeTomethod. If a device is going to a reduced power state, interested drivers generally don’t need to do much with this notification. However, if the device is going to a higher power state, interested drivers would use this notification to prepare for the change by, for example, restoring state or programming a device.In your implementation of

powerStateDidChangeTo, your driver can examine theIOPMPowerFlagsbitfield (described in Table 9-2) passed in to make its determination; this bitfield is derived from thecapabilityFlagsfield of the power-state array, which is described in Table 9-1 As withpowerStateWillChangeTo, your driver should returnkIOPMAckImpliedif it has prepared for the change. If it needs time to prepare, it should return the maximum time required (in microseconds); when your driver is finally ready for the change, it should call theacknowledgePowerChangemethod.Important: The

powerStateDidChangeTomethod is not the place to perform any tasks related to the actual changing of the power state. Such tasks should be performed in thesetPowerStatemethod, which is described in “Responding to a Power State–Change Request”

When your driver is no longer interested in the power changes of other drivers, it should deregister itself to stop receiving notifications. To do this, call the IOService method deRegisterInterestedDriver, usually in your driver’s stop method.

Receiving Shutdown and Restart Notifications

In a driver targeting Mac OS X v10.5 and later, you can implement the systemWillShutdown method to receive notification of an impending shutdown or restart. It’s important to understand, however, that there is nothing your driver can do to prevent a shutdown, regardless of the notification it receives. Your driver is capable of delaying shutdown, but that is strongly discouraged because it can severely degrade the user’s experience.

Do not assume that your driver should implement systemWillShutdown so that it can respond to shutdown and restart notifications by shutting down your hardware. At shutdown time, power is about to be removed from your device regardless of its current state. Similarly, if the system is restarting, your device will be reinitialized shortly and, again, its current state is not important. Most built-in device drivers in Mac OS X do not shut down their devices when the system is about to shutdown or restart and most third-party device drivers should do the same.

Although the majority of device drivers do not need to handle shutdown or restart in any way at all, there are two valid reasons for a driver to run at shutdown or restart time:

The architecture requires the driver to execute code at shutdown time. For example, all drivers that perform DMA in an Intel-based Macintosh must stop active DMA before shutdown can complete.

The driver must run at shutdown or restart time to avoid negative user experience. For example, an audio driver might need to turn off its device’s amplifiers to avoid an audible “pop” when power is removed.

Note: There are other places that you may run code on the shutdown path. For example, if your software has a user-space daemon that runs until shutdown, that daemon can catch SIGTERM, which the kernel sends to all processes at shutdown. In general, try to run your shutdown code as early as possible in the shutdown path.

The systemWillShutdown method is called on all members of the power plane, in leaf-to-root order. A driver’s systemWillShutdown method is invoked only after all its power children have completed their shutdown tasks. This ensures that a child object can handle its shutdown or restart tasks before its parent powers off. Note that it is not necessary to call your driver’s free method when the system is about to restart or shutdown, because all drivers are unloaded and destroyed at this time.

When a driver receives the systemWillShutdown call, it performs the necessary tasks to prepare for the shutdown or restart and then invokes its superclass’s implementation of the method. This is essential, because system shutdown will stall until all drivers have finished handling their systemWillShutdown notifications. Other than postponing the call to super::systemWillShutdown until an in-flight I/O request completes, you should do everything possible to avoid delaying shutdown. Listing 9-2 shows how to override systemWillShutdown and receive notification of shutdown or restart.

Listing 9-2 Getting notification of system shutdown or restart

void MyExampleDriver::systemWillShutdown( IOOptionBits specifier ) |

{ |

if ( kIOMessageSystemWillPowerOff == specifier ) { |

// System is shutting down; perform appropriate processing. |

} else if ( kIOMessageSystemWillRestart == specifier ) { |

// System is restarting; perform appropriate processing. |

} |

/* |

* You must call your superclass's implementation of systemWillShutdown as |

* soon as you're finished processing your shutdown or restart |

* because the shutdown will not proceed until you do. |

*/ |

super::systemWillShutdown( specifier ); |

} |

Keeping Power On for Future Device Attachment

To conserve power, a device whose children have all disappeared is usually considered idle and is told to power off. However, your device might need to stay powered on to allow new children to attach at any time. For example, a bus might need to remain powered on even when there are no devices attached to it, because a new device trying to attach can cause a crash by attempting to access hardware that’s turned off.

The IOService class provides a method that allows you to keep your device’s power on, even if all its power children have disappeared. The clampPowerOn method allows you to specify a length of time to keep the device in its highest power state. If you need to do this in your driver, call the clampPowerOn method before the last power child disappears, as shown below:

// timeToStayOn is a length of time in milliseconds. |

clampPowerOn ( timeToStayOn ); |

© 2001, 2007 Apple Inc. All Rights Reserved. (Last updated: 2007-05-17)